System archetypes are common and usually recurring patterns of behavior in organizations. These patterns almost always result in negative consequences. You can use system archetypes to effectively answer the question, “Why does the same problem occur over and over?”

System archetypes were first studied in the 1960s and 1970s by Jay Forrester, Dennis Meadows, Donella Meadows, and others in the nascent field of systems thinking.

In his popular 1990 book, “The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization,” author Peter Senge explored system archetypes and, along with Michael Goodman, Charles Kiefer, and Jenny Kemeny, documented the most common set of patterns of behavior in organizations that have a tendency of recurring. These systems-thinking archetype researchers leveraged the annotations of John Sterman, a pioneer in system dynamics. The structures and graphical language of system dynamics allowed Senge and his colleagues to document these common system archetypes and make them accessible to the average reader.

Eight system archetypes and their storylines

The eight most common system archetypes are:

Fixes that fail—A solution is rapidly implemented to address the symptoms of an urgent problem. This quick fix sets into motion unintended consequences that are not evident at first but end up adding to the symptoms.

Shifting the burden—A problem symptom is addressed by a short-term and fundamental solution. The short-term solution produces side effects that affect the fundamental solution. As this occurs, the system’s attention shifts to the short-term solution or to the side effects.

Limits to success—A given effort initially generates positive performance. However, over time the effort reaches a constraint that slows down the overall performance no matter how much energy is applied.

Drifting goals—As a gap between goal and actual performance is realized, the conscious decision is to lower the goal. The effect of this decision is a gradual decline in the system’s performance.

Growth and underinvestment—Growth approaches a limit potentially avoidable with investments in capacity. However, a decision is made to not invest, resulting in performance degradation, which results in a decline in demand validating the decision not to invest.

Success to the successful—Two or more efforts compete for the same finite resources. The more successful effort gets a disproportionately larger allocation of resources to the detriment of the others.

Escalation—Parties take mutually threatening actions, which escalate their retaliation attempting to “one-up” one another.

The tragedy of the commons—Multiple parties enjoying the benefits of a common resource do not pay attention to the effects they are having on the common resource. Eventually, this resource is exhausted, resulting in the shutdown of the activities of all parties in the system.

The set of common system archetypes has its own unique causal storyline. This storyline is universal and can be applied to the understanding of individual manifestations inside organizations. For instance, the fixes that fail archetype has the “squeaky wheel” as its main storyline. In this system archetype example, a quick fix is applied to a pain point (or “squeaky wheel”) to reduce its symptom and the “noise” generated by it. The storyline gets complicated when the unintended effects of the quick fix become consequential. These effects start to add to the problem, making the quick fix less or totally ineffective.

Read more:

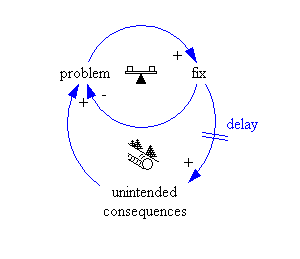

Aside from a storyline, system archetypes have a structure. This structure consists of a number of mostly endogenous variables and feedback loops—one or more of which contains a delay that usually contributes to the unintended consequences of the behavioral pattern, a crucial aspect in understanding social sciences. Endogenous variables are those that form part of the feedback loops that both modify and are modified by other variables.

Three of the common eight system archetypes—limits to success, growth and underinvestment, and tragedy of the commons—contain endogenous variables that act as external constraints to these systems. The structure of these system archetypes is depicted through causal loop diagrams, a tool from the field of system dynamics.

Unintended consequences (Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons)

This diagram (left) shows the structure of the fixes that fail archetype. This structure has three variables: the problem symptom, the quick fix, and the unintended consequence. The flow between the fix and the unintended consequence has a delay and is the main reason for the existence of the archetype. Two feedback loops are present in this structure: a balancing loop for the quick fix and a detrimental reinforcing loop for the manifestation of the unintended consequence.

Archetypes and their applications

System archetypes can be used as a diagnostic tool to better understand the dynamics of a specific set of behaviors that have manifested an unwanted condition.

The theory behind system archetypes is that situations with unwanted results or side effects can be mapped to common behavior models. Given the knowledge available about system archetypes, problem-solvers, in general, can apply its principles and arrive at a rich diagnosis of a situation and plan a recovery. The knowledge base on system archetypes provides guidelines for determining what archetype is at play and, once identified, how to approach an intervention.

From a proactive perspective, system archetypes can be an essential part of planning. A variety of strategies can be tested through the lens of archetypes to identify potential pitfalls and address them in the planning stages when they are easier to tackle. Additionally, system archetypes provide a language to communicate among members of an organization regarding how a particular system is expected to perform. Unintended consequences in system archetypes are well known and can be translated into potential or realized consequences. Having a language to document, communicate, and analyze behaviors provides a useful and consequential framework for dealing with changes necessary to prevent or eliminate negative behavioral patterns. Moreover, once the particulars of system archetypes are mastered by members of an organization, their knowledge can be leveraged to build robust systems immune to their side effects.

If you are curious about how system archetypes can work in the fields of social science or integrative medicine and health sciences, Saybrook University offers programs that focus on students, making sure they reach their full potential, with an academic focus in humanistic psychology to make the world a better place. Learn more by exploring our programs below.

Learn more about Saybrook University

If you are curious about learning how system archetypes can work in the fields of social science or integrative medicine and health sciences, Saybrook University focuses on its students, making sure they reach their full potential, with an academic focus in humanistic psychology in order to make the world a better place, with our programs below.

Find Out More

Recent Posts