Older generations have been revered for centuries for their expertise, secrets, and experiences. Researchers have studied for years what makes someone live longer—convinced that just maybe there is a trick we haven’t figured out yet. And advertisers love selling us the latest Mediterranean diet, red wine trend, or higher altitude methods that will keep us all alive for longer. This search for immortality makes sense when you remember that in 1940, the average life expectancy was around 60 years old. So when someone lived to 89, they were special—someone to be respected by children and adults alike. Stories about what they had eaten, drank, how far they walked, how they loved, and how they truly lived were shared throughout families and communities.

But in 2020, when the average life expectancy in the U.S. is 78 years, old age seems like old news. We’re less impressed and less curious about what these older generations have seen or done—apathetic to their presence.

Coronavirus revealed many inequities in our cultural system, and perhaps none so grave as the way we treat our elderly. More than 60% of those who have died from COVID-19 in the U.S. were 75 or older, and almost 80% were age 65 or older. It’s not just that the disease targets the older generation—it’s the lack of protection that society has provided them. Even with the news surrounding the impacts of coronavirus on our older populations, there is no shortage of disinterest in caring for them and their well-being.

Valuing older generations is not just about learning what they know but also is equally about their right to a future too. Respecting older generations means treating and caring for them well. In humanistic psychology, each individual’s experience is valued equally. Yet as society continues to value youth and economic progress, Baby Boomers and the Greatest Generation are dying at higher rates during this pandemic.

Valuing older generations is not just about learning what they know but also is equally about their right to a future too. Respecting older generations means treating and caring for them well.

Different strokes

Both of my grandmothers lived in my childhood home before their passing. They continued to be an important part of our day-to-day lives—no matter their physical conditions or deterioration. We talked about my day, about their days—presently and in the past. This intimacy and approach to aging and relationships didn’t start overnight—it was a value system in my family. Growing up, I wasn’t aware that this wasn’t the norm. Generational respect is not a given.

Depending on how one was brought up and what one places value in, treatment of our elder generation can vary. In any discussion of human behavior, especially from a humanistic lens, one must remember: Not everyone lives the same experience.

Theopia Jackson, Ph.D., co-chair for the Department of Humanistic Psychology, chair of the Clinical Psychology program, and the president for the Association of Black Psychologists, Inc., explains that as a humanistic psychologist, it’s important to look at what it means to be human in context—in a socio-political-economic context.

“It’s important to acknowledge that there is not one way to be in regards to how we treat older generations,” she says. “In our Western thinking, we are trained to think either/or, right or wrong. But what humanistic principles are saying, we must do both/and because one person’s lived experiences and their values and practices are just as important. Certain socio-economic factors contribute to how we treat our elders and cultural traditions that directly affect how we treat our older generations.”

Take, for example, the ravaging of the nursing home population during COVID-19. Current statistics suggest that of the U.S.’s 155,000 coronavirus deaths, more than 40% have been residents or employees of long-term care facilities and nursing homes. Before we explore what this says about our values as a society, it’s important to note that even being able to send a loved one to a nursing home is a privilege.

Sending older people to nursing homes has become a rising practice, but looking through the long lens of history, it is a relatively new concept. In the past, most cultures shared one residence spanning three to four generations—simply out of necessity. From birth to death, you lived at home. Not only did you live at home, you added value, you were cared for, you were listened to.

But as families moved up and out, communities began the sprawl and generations began to separate. However, as Dr. Jackson goes on to explain, when long-term care facilities are working, they offer a valuable resource.

“They’ve probably saved many people; probably improved the quality of life for many who are aging, to be able to be in a safe place, a caring, loving place, surrounded by their own generation,” she says. “This can affirm them again in this new phase because the things that are of interest for them are similar.

“Yet we also know that in a capitalistic society, in a society that is born from white supremacist ideology and capitalism, there is a perpetuation for, ‘Me, me, me, me, me,’ a value for youth and individuality. All of a sudden having to care for your loved one can be a burden, and sending them away can alleviate that.”

In over a dozen states, more than 50% of deaths related to COVID-19 were residents of nursing homes or assisted living residences—as high as 80% in Minnesota and West Virginia. What was supposed to be a safe haven for older generations turned out to be a festering sore during the pandemic. The ACLU reports, “In some cases, facilities have not only failed to report, but have actively hidden deaths from residents, families, and the government.” The way systems have failed so many of our older generation during this current pandemic can be seen in the lack of care and assistance that nursing homes have been able to provide. You care for what you value, so this can be seen as a direct representation of our social and cultural values and practices. But what’s being overlooked is the ways in which this pattern and loss will negatively impact younger generations as well.

It’s important to acknowledge that there is not one way to be in regards to how we treat older generations...because one person’s lived experiences and their values and practices are just as important.

Where were you?

Even before it was written down, history has always kept us alive. Oral history has been a key part of social evolution and resilience since the beginning of time—we have survived predators, natural disasters, plagues, and dying crops because someone is there to remember what happened in the past and how they lived through it.

“Stories are better than simple explanations for history. Their content is richer and more applicable to a broad range of circumstances. Older people love to share stories and those stories are well worth listening to, if only for the value of hard-won insights over a long period of time,” says Drake Spaeth, Psy.D., co-chair of Saybrook’s Department of Humanistic Psychology.

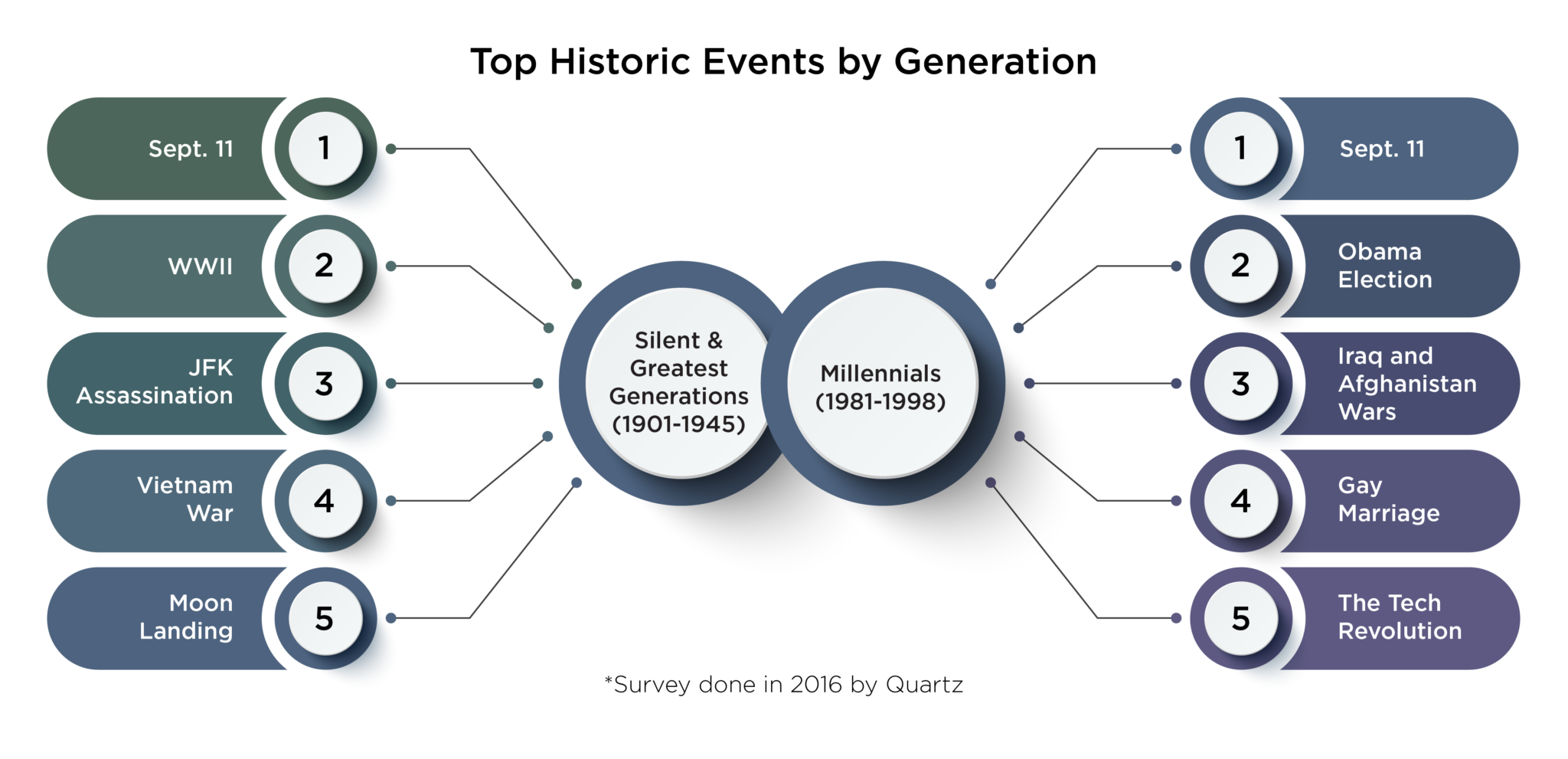

Our grandparents and elders can tell us what getting running water was like, how many friends perished in Vietnam, where they were when the Challenger exploded, when JFK was shot, what their first ride in an automobile was like—a vast array of big events that have marked their lives. But the small events provide some of the most important bits of advice too—a perspective that has weathered time and challenges. Learning how to live through the difficult and thrive in different situations proves a spirit that is valuable no matter the year, decade, or circumstance.

“What older individuals get from aging is an increasing openness through life experience to universal reality,” Dr. Spaeth says. “They more easily recognize patterns among events that allow for a depth of foresight, intuitive understanding, and an array of coping resources that were not available to them when they were younger.”

It’s not just that they have seen more. It’s that they connect more—they can put the pieces together for us. We often forget that we too will have these large events to mark our time—9/11, the coronavirus, Obama’s election—and we’ll be ready to share what we learned personally and as a society too. But will anyone want to listen?

“Elder is not simply a term of endearment or a term that one holds because they’ve gotten old. We learn of the idea of the term elder from our African traditions,” Dr. Jackson explains. “Like with other indigenous groups, including Native Americans, an elder means that you serve a role in the community or in the village. And most times they’re the wisdom keepers. They are the protectors. They are the storytellers.”

What older individuals get from aging is an increasing openness through life experience to universal reality.

Older than all of us

One of these valuable storytellers is Jeanne Calumet. You may have never heard of her or her story, but born in 1875, she did the unthinkable and lived through it all.

And lived.

And lived.

For 122 years.

For 122 years, she managed to outlive lovers, friends, children, neighbors—everyone. Recently, a few researchers have suggested that her age was fraudulent and she had begun lying about it much earlier in her life. While the evidence suggests that she was truly 122 years old—an outlier—in a world that equates beauty over age, prioritizing youth over all else, it’s difficult to believe that someone would willingly choose to lie about being older. But perhaps this high value on youth and diminishing value on age is a new phenomenon.

Relationships and mentorship between younger and older generations have been a large part of a variety of cultures throughout history. From Native Americans to African traditions, to quinceaneras and presentation balls for affluent white young men and women, initiations into the next part of life abound. Generational progress has long been praised and valued with older generations leading the young, but the value has been placed more on youth and less on what we can learn from our elders.

“In a Jungian or depth psychological sense, the adulthood initiation is archetypal—universal in the human psyche, a thematic pattern of striving that has evolved throughout human history,” Dr. Spaeth explains. “Without an adult mentor, that archetypal yearning is extremely vulnerable to the unconscious shadow—the repository of repressed aspects of humanness with which we are uncomfortable.

“Sadly, the wisdom of elderhood seems to be more neglected, and (alarmingly) even despised, in comparison to indigenous contexts where popular recognition of that wisdom would earn one honored places and roles in society,” Dr. Spaeth adds. “This disconnect impedes the meaning of formal and informal rites of passage or initiations into the experience of adulthood.”

The disconnect

We are living and working longer, which provides opportunity for older generations to continue contributing and affecting society for many more years. Our current president is 74, and the Democratic nominee who hopes to unseat him is 77 years old—meanwhile the resident favorite Supreme Court judge somewhat surprisingly passed at a spry 87 years old while still working doggedly, and the Speaker of the House keeps order at 80.

Yet in the demographic making up the electorate that will choose who leads for the next four years, one in 10 voters will be in Generation Z—meaning between the ages of 18 and 23. The generational divide between those leading and those living seems to continue to expand.

As the way we experience the world continues change, the frustration from the generational divide grows. “It may also mean that younger people may find it more difficult to attain positions of leadership, increasing the tension among generational cohorts who are coming of age and craving more meaningful responsibility and participation in social contexts. Understandably, resentment and frustration arise among younger generations for what they regard as the legacy and consequences of past mistakes when they are in less empowered positions with regard to making substantive and sustainable change,” Dr. Spaeth adds.

But by listening, caring for, and incorporating the world through a multi-generational lens—like generations before us—every generation can gain insight to thrive well into the future. The only difference between the young and the old is time. And if the young are lucky, they’ll one day understand what it’s like to be a part of the older generation.

Learn more about Saybrook University

If you are interested in learning more about the community and academic programs at Saybrook University, fill out the form below to request more information. You can also apply today through our application portal.

Find Out More

Recent Posts