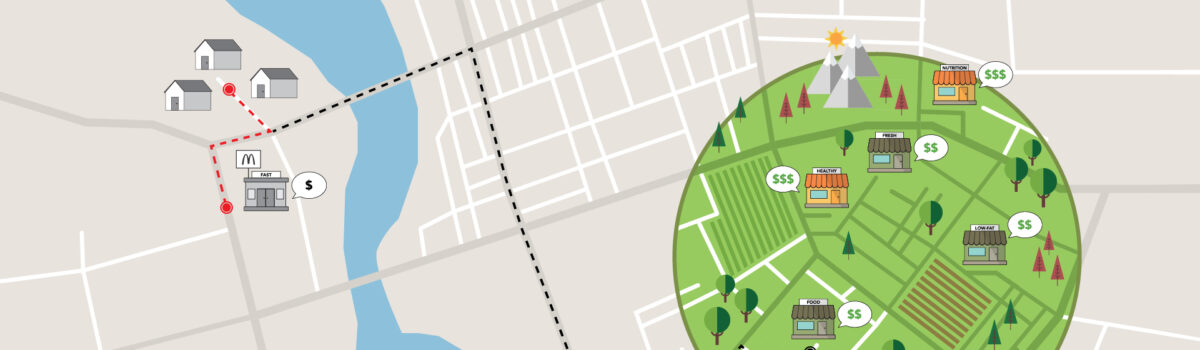

welcome to America, where there are more than 38,500 grocery stores, the unemployment rate sits at its lowest level since 1969, and 77 percent of the population is equipped with smartphones—yet 23.5 million people live in food deserts, areas with no easy access to fresh food options. With so much abundance, job growth, and technology in the U.S., one would think a problem as simple as food accessibility would be eradicated by now.

It’s not.

To qualify as a food desert, at least 500 people or 33 percent of the census tract’s population must reside more than one mile away from a supermarket or large grocery store. For people living in food deserts, this can often mean a three-hour roundtrip to the store, as residents lack their own form of transportation. With their food options severely limited by what local stores like corner stores, bodegas, or liquor shops stock, food culture becomes one of convenience and cost. According to the USDA, this can lead to the residents having nutritionally poor diets that can lead to diabetes, obesity, and heart disease at astronomical rates.

“Your zip code is more telling about your life expectancy than your genetic code,” says Lori Taylor, a clinical dietician with 24 years of experience and a faculty member in Saybrook University’s Integrative and Functional Nutrition program. “You’re a product of your genes and your environment, and your environment informs how your genes will be expressed. When we have such disparate living environments for people in the U.S., especially children, we’re going to get very different results.”

The solution seems simple: build more grocery stores in those neighborhoods. Yet setting up a new supermarket may not even do any good. A 2018 report by City Lab shows that when new grocery stores open in less-advantaged neighborhoods, including food deserts, it has little impact on the eating habits of low-income households, who are most likely to live in food deserts. This means people will still buy the same foods they’re used to, which are mostly highly processed grain-based products.

“Food is at the intersection between environment, health, medicine, and nutrition,” Taylor says. “It is how we get our nourishment to survive, and it’s directly reflective of what our living environment is like. So anytime we can improve the quality of people’s food, and the variety and the taste and the experience, it can bring healing to people.”

Where do we begin? How do we work on improving overall health and combating food deserts? The answer requires a community shift in thinking and a more holistic look at what it means to be healthy in America.

It’s more than just an issue of access to food

The healthy food that people need isn’t processed in a factory. It’s cultivated in the earth, and born from soil, water, and sun.

Yet the reality of farms is in direct juxtaposition to this image. Only 2 percent of U.S. cropland is used to grow nutritious fruits and vegetables, according to a report from the Union of Concerned Scientists. The majority of the cropland that is used for the food we eat is dedicated to wheat, corn for sweeteners, soybeans, peanuts and oilseeds, corn, and grain.

“We spend 21 billion dollars annually on farm subsidies, mostly to grains and oils that feed livestock and make processed food,” Taylor says. “And we spend 7.1 billion dollars for the Center for Disease Control trying to combat the various diseases that we’re subsidizing yet trying to erase.”

Beyond a lack of investment in the food we grow, the fruits and vegetables that are available for purchase are expensive. While prices for fruits, vegetables, dairy, and meat remained the same from 1990 to 2007, prices for soft drinks and fast foods declined during that same period, meaning it is now cheaper to purchase “energy-dense” junk food than it is to buy fruits and vegetables. This makes a huge difference for families on a tight budget.

“When you’re someone who has limited income and you’ve got a family to feed, are you going to spend three dollars for a pound of broccoli or are you going to spend 99 cents on two boxes of macaroni and cheese?” Taylor asks. “If you’re buying for calories, that’s what you need to do, you need to buy the macaroni and cheese. A lot of people just don’t get that because they’re not in the place of having to make those decisions on a daily basis.”

These types of buying decisions are only made worse by other constraints. Buying fresh food is not only a financial investment but an investment of time as well. Going to the grocery store and preparing and cooking food takes time that a lot of people just don’t have. It is not a reality for parents working multiple jobs to pay the bills while also taking care of their kids.

Even if people are able to get easy, quick access to fresh food, they need to know what to do with it. Generations of families have learned to live a certain way. They may never have been exposed to good nutritional habits, or are not aware of techniques for making timely, affordable meals from fresh, raw ingredients. Communities don’t just need access to quality food, they need to be educated about nutrition in an approachable and accessible way.

“I really do believe that it comes down to education,” says Jeannemarie Beiseigel, Ph.D., the program director of the Integrative and Functional Nutrition program at Saybrook. “The message somehow has to get there, and we need to teach people. It comes down to their exposure and awareness.”

Down South at Bonton Farms in Dallas, Texas

This education component is exemplified by the efforts of a small community in southern Dallas where the neighborhood of Bonton is overcoming generations of adversity and poverty.

Bonton is classified as a food desert: 63 percent of residents do not have transportation, the nearest grocery store is three miles away, and there is only one local beer and wine store from which to purchase food. With the rates for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, stroke, and cancer all higher than Dallas as a whole, something needed to change.

Enter Bonton Farms, which was founded to combat the high rate of disease within the community. It grows fruits and vegetables, and recently opened a market that serves breakfast and lunch using ingredients grown there. The Market at Bonton Farms also offers a variety of enrichment classes and workshops to help inspire and educate people on healthy lifestyle choices.

Betty Murray, a Saybrook student in the online Ph.D. in Integrative and Functional Nutrition program, volunteered at Bonton Farms as part of her coursework. Despite the completion of her project, she continues to help out at the farm, and is even offering the resources of her nonprofit, the Functional Medicine Association of North Texas, to help with community education. The group is comprised of health care providers in the North Texas area, and is currently working to provide pop-up clinics with medical screenings and classes about nutrition at Bonton Farms.

“As a community that wants to help, it’s great that we can come in, but we need to recognize that the most valuable changes are getting basic human needs met in a way that’s safe and effective for the people that live there,” Murray says. “And when you do that, then that community can actually tackle greater problems. But they can’t tackle greater problems until their very basic human needs are met.”

This line of thinking supports the need to avoid quick-fix solutions (like constructing a grocery store) and to instead invest in long-term solutions that empower the community and create lasting education and change. As integrative functional nutrition encompasses several models—like medical nutrition, whole foods, food science, socioeconomic concepts, and community nutrition—professionals like Murray are poised to provide these communities with the accessible, affordable, and approachable education they desperately need.

Shifting the integrative nutrition and functional nutrition paradigm

Integrative functional nutrition in the past has been predominantly for people with the resources to pay for this type of care. But Saybrook’s program seeks to narrow this social gradient in medicine by incorporating issues of accessibility into coursework and encouraging students to broaden their own worldviews and pursue a more holistic approach to nutrition.

“One of the things that is most valuable to me at Saybrook is that we pay attention to the social justice side of health,” Murray says. “The fact that Saybrook keeps that underpinning of what the school was started around and puts it into the Integrative and Functional Nutrition program is so important because we as professionals do have the ability to influence all aspects of health in health care. If we ignore that, then we’re doing nobody any good.”

Part of that effort is to keep education approachable and accessible. And since supporting the community is so paramount to this effort, professionals must also increase their exposure and knowledge about the areas they are serving.

“Integrative functional nutrition uses an individualized approach. In communities, you’re not going to be able to address everyone’s individual personal medical history, so you have to do your research,” Dr. Beiseigel explains. “Where are the grocery stores in that community? What is the average education level of people in the community? What is the job background or average income level? What are their major health issues? What current resources are available to them?”

Growing from the ground up

As Murray learned from her time at Bonton Farms, it’s the small things that can lead to big changes. She shares the story of a man who grew up in Bonton, moved away, and then came back to help support the community.

“I asked him what he wanted for the area of Bonton and it came down to some very fundamental things,” Murray says. “He said, ‘I want my neighbors to have enough food.’ His needs and desires were so basic. What was heartbreaking to me, and also just eye-opening, is that we can have these lofty goals, but at the very end of the day, providing those fundamentals is the important part.”

Those basic needs are at the heart of the issue: they reflect a culture and lifestyle that was born out of extenuating external and systematic factors. To address food deserts, we can’t just increase access to fresh food; we need to change an entire community’s way of life through increasing public transportation, affordable housing, wages, education, and policy.

To do so will require an all-hands-on-deck approach, more than just supermarkets or even urban farms. It’ll take a village to help the community heal itself, to have America, a country with abundant resources, ensure food accessibility for all.

If you are interested in learning about graduate-level programs available at Saybrook University, fill out the form below to request more information.