The coronavirus calls for dramatic behavioral responses to contain a pandemic of uncertain magnitude. Among the responses is the restriction of social contact through self-isolation so as to reduce likelihood of contagion. For psychology, this introduces a paradox. Isolation, as a theme in psychology, has preceded the coronavirus. One major contribution to psychology has been in understanding the importance of social contact for both physical and psychological, health and well-being (Caplan, 1974; Novotney, 2019). Social isolation has been shown to be a factor in weakening immune-competence and precipitating health breakdowns, ranging from cardiac and respiratory conditions to injuries from accidents. Breakdown is a generic term, including any form of mental or physical pathology. In epidemiological studies, the term is sometimes measured by number of medical service visits, excluding pregnancy. This provides a label for identifying overriding factors, like poverty or social isolation, which may contribute to illness that is expressed in diverse forms (Berkman et al., 2014). For the most part, people linked closely to others are better able to stay well. Evidence for this is summarized in Berkman et al.’s (2014) review of this prevalent theme in social epidemiology. Recognition of the importance of supportive networks has historical roots. Sydney Cobb’s 1976 presidential address to the Society of Psychosomatic Medicine states:

The conclusion that supportive interactions among people are important is hardly new. What is new is the assembling of hard evidence that adequate social support can protect people in crisis from a wide variety of pathological states: from low birth weight to death, from arthritis through tuberculosis to depression, alcoholism, and other psychiatric illness. Furthermore, social support can reduce the amount of medication required and accelerate recovery and facilitate compliance with prescribed medical regimens. (p. 310)

Since this time, there has been increasing corroboration of the evidence linking supportive ties to health maintenance. The spread of isolation and loneliness has led to documented accounts of increased behavioral disorders, including depression and suicide attempts (Putnam, 2000). It has also led to increases in arthritis, diabetes, respiratory disorders and failures to respond to cancer treatments (Novotney, 2019).

Evidence on the extent of mental health consequences associated with isolation during the coronavirus pandemic is still being assembled. The director of the Department of Mental Health and Substance Use at the World Health Organization has drawn our attention to the psychological distress likely to be increased by the coronavirus crisis (McKeever, 2020). A large number of people are worried about their own health and the health of their families and are frightened about their loss of ability to hold a job. Among them are people who have had a history of mental disturbance. For them, the new crisis precipitates exacerbations (Solomon, 2020). The coronavirus is bringing with it substantial casualties and a significant degree of personal trauma felt by those bearing the illness and by those serving them. The effects extend to everyone and are exposing many unresolved problems of inequality and priorities of government policy. Responses to the coronavirus involving reduced social contact can surely add to the health effects of isolation. Paradoxically, the responses to the coronavirus offer both a chance for many to survive it and an opportunity to build a healthier society for the future.

Sensory deprivation and social isolation

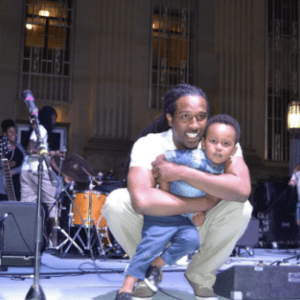

The field of psychoneuroimmunology has added biological understanding to the question of how the immune system apparently recognizes, through neural and other physiological mechanisms, that one is loved (Azar, 2001). More to the point, there are studies suggesting the wide range of contacts needed to sustain healthy functioning. For some, the restrictions of the pandemic include a lack of tactile sensation—not divorced from the meanings ascribed to contact more generally.

Hugs and handshakes reinforce a sense of connection. Whatever the source or intent, isolation and separation as practiced in containing the spread of coronavirus add to vulnerability.

Isolation has been shown to increase memory loss in older people (Shankar et al., 2013). Early studies of people cut off from sensory stimulation (visual, auditory, and tactual) show that within a relatively short time, their cognitive capacities falter and some begin to hallucinate (Stribling & Essau, 2011). Prisoners in jail who are subjected to long stays in social isolation units show similar symptoms of disorientation (Smith, 2006). Totalitarian governments have used social isolation in painful experiments to wipe out former beliefs and replace them with official propaganda (Lifton, 2012; Taylor, 2004).

Solitary confinement was frequently used in colonial boarding schools as a punishment for American Indian children. Forced separation from families and from signs of tribal culture caused depression and illness, with more students dying than graduating from the schools (Estes, 2019). Classic studies of attachment and maternal deprivation show infants deteriorate rapidly if deprived of physical contact with a mother figure (Ainsworth, 1982; Bowlby, 1973). While social distancing is different from sensory deprivation, the latter does suggest harm from the former for some people under some conditions.

Empirical findings on the effects of supportive contacts

Human interconnectedness is multi-faceted and is better conceived as a theme of human existence than as the sum of component parts. It ranges from sensory transactions to affiliations with families and other groups. Physical touch is an important part of contact. In the classic 1965 experiment conducted by Harlow, researchers separated infant rhesus monkeys from their mothers and bottle fed them with a mechanical device. For one group, the bottle was held in place by a metallic mesh. For another group, the bottle was held in place by a soft cloth covering. The wire mesh group deteriorated quickly, while the cloth substitute mothers provided the contact apparently needed at this stage of development. Even the lactating wire mother was deserted after feeding, in favor of a dry cloth substitute (Harlow, 1965). Tactual sensations have a special place in human bonding.

More recent research has shown the value of physical touch when working with children in institutionalized settings with AIDS patients and with breast cancer patients. The mechanism appears to be a lowering of cortisol level and an increase in natural killer T cells (Pilisuk & Parks, 1986). Decline in the incidence of direct touch has been noted in the United States (Jones, 2018). The Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2020) reports that neglected children suffer worse consequences and subsequent developmental impairments than those who have been abused. Touch deprivation is but a part of the larger problem of social isolation and threadbare networks of social support.

Events that isolate people or cut off a significant relationship puts one at a higher risk of health breakdown (Pilisuk, 1982). In this sense, the accommodations needed to contain the coronavirus can predictably preclude the contact with important caring relationships needed to reduce our susceptibility to illness (McKeever, 2020). If this contact, so needed for health and well-being, is placed out of reach, the necessary isolating response may be increasing our susceptibility to other illness. When we are requiring social distance, isolation in homes, and disruption in contact among friends and family members, can psychology help us to reduce the anticipated toll? What does the field of psychology have to say about dealing with this paradox?

First, psychology and related disciplines have confirmed the extent of the relation of social support to physical and psychological health maintenance. Consistent with findings from the laboratory, larger scale studies confirm the importance of social ties in limiting breakdowns in physical and mental health (Pilisuk & Minkler, 1980). A classic example came from sociologist Emile Durkheim’s (1951) study of suicide, finding its rates to be highest among people with low integration in their communities. Persons who develop schizophrenia, or who are admitted for any form of psychiatric hospitalization, are likely to share the fact of fewer supportive social ties (Lim & Gleeson, 2014). Social linkages among people are indirect communication but are also intangible exchange of resources. With this broader view, insufficiency of such ties comprise a definition of social marginality, which has been linked to most forms of physical and psychological pathology (Foster et al., 2018; Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2020). This same factor frequently characterizes the victims of suicide, alcoholism, multiple accidents, and hypertension (Novotney, 2019; Pilisuk, 1982; Stravynski & Boyer, 2001).

A study of coronary disease among Japanese men living in California showed those with traditional close-knit Japanese family ties to be at significantly lower risk than those who had been assimilated (Marmot & Syme, 1976). Another large-scale longitudinal study of residents of Alameda County, California, examined social and health status at one point in time and followed their records of illness and death over a subsequent nine-year period. It showed that disease, morbidity, and mortality rates, from all causes, were related to an index of the individuals’ personal ties at the start of the study. The relation appeared for both sexes, for all ethnic groups, and across socio-economic classes (Berkman & Syme, 1978; Pilisuk & Parks, 1986). For those who do fall ill, social support is important in fostering compliance to medical treatments. These seminal studies have been replicated and expanded to document the scope of conditions affected by isolation and by the relation of isolation and of support to resilience (Novotney, 2019; Solomon, 2020).

The importance of supportive ties is highlighted in studies of the death of a spouse. Among the newly bereaved, the rate of coronary mortality, particularly among men, is substantially higher than that found among others of their age group (Pilisuk and Parks, 1986). Bereavement proves a time for unusually high susceptibility, not only to coronary disorders, but to all forms of health and mental health breakdown. These adverse effects, however, were shown to be absent when the individual maintains even one close supportive relationship (Pilisuk & Parks, 1986). A study of circumstances surrounding 275 sudden deaths reported in newspaper accounts found that the most frequent category (135 deaths) to have followed upon an exceptionally traumatic disruption of a close human relationship or the anniversary of the death of a loved one (Pilisuk, 1982; Pilisuk & Parks, 1986). Escalating mortality rates during the coronavirus pandemic are likely to demonstrate similar consequences for bereaved survivors.

The effects of social disconnection on health cover an amazing diversity of circumstances. Surely there are different circumstances that may lead an individual to be prone to one form of illness rather than to another. Asthma, cardiac disease, accidents, suicide, or depression all have distinguishing risk factors. The argument here is that weak or disrupted ties fall upon individuals who already have their own ways of reaction to the stressors they face and with inadequate support, a breakdown will be more likely to occur. The wide diversity of diagnostic conditions should not detract from the broader conclusion: social connections are vital to our health and well-being, and coronavirus is limiting them.

Limitations of empirical findings

The warning that social distancing is likely to portend negative health consequences is clearly supported by early empirical evidence and reinforced by contemporary studies (Whitley, 2017). Fortunately, that is not the only contribution psychology and related fields contribute to our understanding of human resilience. The consequences of social disconnection mentioned so far have been developed through empirical studies, some of animals or humans in controlled settings, and some equally powerful, comparing populations living under different conditions. The heritage comes from an era in which psychology strove to be a science by copying methods identified with the physical sciences. The importance of social connection, loneliness, or losses in one’s network had of course been noticed by authors, artists, and indigenous healers (Putnam, 2000). However, the major formulations were part of an empirical psychology that was dominant through the 1960s, when it ran into criticism for its Western biases. Unwittingly, the field of psychology became part of a colonial mindset, helping the larger society demand conformity to its norms from diverse or deviant children or victims of conquest. Mainstream psychology also displayed a preference for measurable behavior over less tangible conscious or even unconscious experience. And in an effort to appear scientific, psychology inadvertently eschewed a deep value and appreciation of its core subject matter: the human being.

Virtual contact and humanistic psychology

Humanistic psychology has been one of the enduring voices of this criticism of an overly mechanistic, quantitative, and normatively biased field of psychology. It spawned methods that reach into the subjective and have a bearing on response to coronavirus. The new circumstances, an anti-epidemic strategy requiring physical separation, oblige us to dig into other contributions from psychology and from the social sciences. I have grouped these other contributions under the rubric of “humanistic psychology.” Humanistic psychology has a rich legacy of therapy and research that lies beyond the scope of this paper. What is relevant here are roots in ethnographic anthropology, ecological psychology, feminist psychology, existential therapies, and humanistic sociology. One unifying contribution underlying humanistic psychology is an appreciation and understanding of phenomenological experience.

The phenomenological approach can be described as one that focuses upon the study of consciousness and the content of one’s direct experience (Husserl, 1999; Merleau-Ponty, 1962). These contributions deal with our experiences, the reality which each of us constructs. They include the cognitive maps of kin and other associates, both close and distant. These inner libraries, carried within us maintain identity and buffer us from destructive levels of stress. They sustain us with images of our connection with and appreciation for others, as well as with our familiar habitats and ecology. It is not only the physical contact and face-to-face engagement with people that sustain us. It is also the internalized depiction of our experience. This inner reality can be used to enhance our sense of connection with others, even in the absence of direct contact. It can be used to vitalize our continued participation in virtual activities that keep us connected and provide outlets for our participation in preserving a sustainable world.

Advances of internet communication have offered one tangible example of adaptation: support groups for many health and personal needs are now conducted on the computer screen. Some are professionally led, and some are informal and spontaneous. They may provide synchronous or asynchronous participation and offer opportunities for people facing rare conditions to find each other. They provide opportunity for family gatherings, even among geographically dispersed families. One consideration is that access to equipment and an internet connection is not guaranteed for everyone (Gary & Remolino, 2000). Just how meaningful virtual communications can be to the meaning and richness of human experience is a question raised by humanist scholars. Schneider (2019) clarifies a distinction between authentic communications of real people and the artificial messages designed by algorithms. The latter undermine the vital creative insights and criticisms so necessary for social change.

Within the humanist framework are persuasive philosophical arguments about the existential centrality of the symbolic worlds we create (Husserl, 1999; Merleau-Ponty, 1962). The framework has included departures from deterministic outlooks, which may curtail the possibilities for newness in our lives. Psychotherapeutic approaches, such as nondirective therapy, have evolved as methods in which the client does the work of uncovering their own potentials to create something new (Rogers, 1961). The plethora of experiences that can be harnessed into promoting deep change have extended into music and dance therapies, visualizations, and meditation. Creativity has been moved from nonessential characteristics of life, to the central task of being human (May, 1975). Rather than viewing creativity as an exceptional talent, we have rediscovered it as an aspect of everyday life (Richards, 2007).

One important strand of this outlook is humanistic sociology. Traditional sociology, like traditional psychology, has focused upon observations that can be measured. They tell us what is but not what could be. The goal of humanistic sociology is an emancipatory potential for such possibilities as peace, love, and social justice. It works toward securing a voice for those victimized by neglect and injustice (Du Bois & Wright, 2002).

Humanistic modes of thought are useful in matters that introduce great uncertainty. The current pandemic is such a situation (Crockett et al., 2018). Humanistic psychology enhances the visibility of caring. Moreover, the experiential emphasis welcomes deep compassionate concern at a spiritual level, for people and places we will never know on a direct level. Humanistic psychology has something important to offer in going beyond deterministic frameworks and emphasizing subjective, phenomenological experiences. The approach has something significant to say about how people can accommodate positively to the changed environment imposed by the coronavirus.

The passion and creative power to build something better

At a time of relative isolation, humanistic orientations can be harnessed to capture the value of quiet and of looking within. In so doing, we find a measure of respite from the overstimulation to which we have grown accustomed and a deeper look into ourselves. Our inner life can hold on to deep connections with our communities, with the natural world, and with the future yet to be attained.

The loss of close, cuddly connections is real, but so too are our passionate connections with people that continue to be carried from within. Even the homes, shops, and landmarks that defined communities have evolved into a psychological sense of community (Sarasson, 1988). These settings are kept alive in our imagination. The potential relief from overstimulation provides a motivation to honor the value of quiet and to recall the depths of renewal that we gain from contacts in the natural world. Part of our loss of the noisy world of direct contact creates a space to become reacquainted with ourselves. Hopefully, the credence that we give to our experience of what really matters helps us to harness the world of our dreams.

Finding community and solidarity through other means

We cannot help but be impressed by the creative ways people find to maintain not only the physical necessities of life, but also the social affirmation coming from friends, neighbors, and agencies. We are traveling less, consuming less, walking more, conversing electronically with family and friends more frequently, and enjoying contact with local nature and home gardens (Nguyen & Animashaun, 2020). People are finding creative ways to check the immediate needs of neighbors, including elders living alone (Damron, 2020). As people sharply cut travel, we notice the air a bit clearer, the waterways a bit less contaminated, and the roads less congested (Regan, 2020). We are reminded that the sacrifices needed to assure a viable planet should not have to wait for a pandemic, but rather should be on our minds always.

The learning opportunities emerging from physical isolation are not available to large portions of our population. Some lower-income, working families have no choice but to continue to live in crowded conditions, to continue to work in high-risk situations, and to stretch their time to care for elderly parents or children who would have otherwise been in school (Vesoulis, 2020). Many others have felt the impact of losing their job, and with it, their health insurance and income needed to support their families. In an eight-week period beginning in mid-March 2020, more than 35 million Americans applied for unemployment benefits (Tappe & Luhby, 2020). The economic and psychological consequences of such losses are detrimental (Ananat & Gassman-Pines, 2020).

For those of us who are able to find meaning in our ability to cope, we are faced with the realization that combating the virus requires reaching out to those who lack the necessary resources, as demonstrated by the current occurrences of community mobilization and mutual aid networks (Hogan, 2020). The strengths we gather from the humanistic tradition of creative imagining serve us in personal coping. Such individual adaptations need to be augmented by work with and for others. Collectively, we will need to apply our awareness to those deteriorating conditions of the planet that give rise to the proliferation of pandemics for which we are unprepared.

Interconnectedness with nature

A persuasive link has in fact been made between the origins of this virus and climate change. The UN’s environment chief Inger Andersen said:

There are too many pressures at the same time on our natural systems and something has to give … We are intimately interconnected with nature, whether we like it or not. If we don’t take care of nature, we can’t take care of ourselves. And as we hurtle towards a population of 10 billion people on this planet, we need to go into this future armed with nature as our strongest ally. (Carrington, 2020)

We are all interconnected, whether it be in working together to slow climate change or in protecting each other from this virus through social distancing and staying at home. Both climate change and a pandemic are problems that require us to work together with respect for nature.

Creating a future

Activism from home relies upon harnessing the potential of inner experience. It is needed on several issues. People at higher risk in particular are limited in their ability to join marches and demonstrations, visits to legislators, and knocking on doors to encourage others to vote. But meetings on big issues have turned to Zoom, and organized post-carding and phone banking events are drawing people to the sense of purpose from cooperative action on superordinate goals. Major shocks to a social system offer opportunities for drastic change (Klein, 2007). For those concerned about the world after this pandemic, it is important to recall that the change may be toward a more compassionate world. But it could also portend surrender to an authoritarian ruler, promising to restore order while moving toward a dystopian (technologically monitored and controlled) militarized state. This dark outcome is currently happening with Prime Minister Orban in Hungary and is viewed favorably by anti-immigrant movements in other countries (Tharoor, 2020).

National budgets reflect a nation’s values. When we find the Centers for Disease Control underfunded, insufficient hospital beds, lack of ventilators and protective gear for courageous doctors, nurses, and health care workers, we should reflect upon whether the 53% of the federal budget spent by the military is doing what is actually needed to promote our health and security (Li, 2020; Lindorff, 2010). Some who have long been dismayed over harmful social systems were too busy to demand their change. Now the virus has exposed the harm of inequality and the futility of finding scapegoats to hide the need for real social change.

We know that economic inequality has an even stronger effect upon health within a country than overall economic level (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009). We are aware now, more than ever, that priorities should have favored the search for cures and the prevention of disease and that the policies that might have gone to improve the quality of our lives have been slighted. Despite physical barriers for advocacy, the message we can deliver to policymakers has become clearer. Moreover, the principles underlying successful citizen participation remain valid, even while indirect means of contact need to be emphasized (Pilisuk et al., 2004).

Looking forward

Experience that accepts existential uncertainty and accentuates creativity is an important ingredient for coping in ways that build a newer and more adaptive reality. A self-concept that emerges with belief that disaster can be faced is an instrument for change. Creativity can be used to envision a better future and to bring it into being. Time spent in solo contemplation, devoid of customary distraction, leaves opportunity for developing a sense of agency. The gaps in our lives required by social distancing can be filled in part by novel ways to come together, in our devices and in our minds. These propensities are critical components for building a level of organized social action so needed to bring about a safer, healthier, more peaceful, and sustainable world. The empirical findings on pandemics and violence are daunting. Hopes lie in our inner capacities to conceive and to create a kinder world.

Finally, just as we seek creative means to fill our home-sheltered lives with personal contacts, some among us find ourselves with time to join in activities to build a more humane world. Our discussions with colleagues, the petitions we sign, and our letters to elected officials are all part of the revolution in societal health care. Through home-scale activism, we can remember how interconnected we are. A case of the virus in Iran or in India, in a prison or in a nursing home, increases the risk of cases in Seattle or New York. Countries whose public health systems have been demolished by economic sanctions pose a risk beyond their borders. Everyone who needs testing, a place for shelter, and food is a part of our human family. It is for us now to promote the promise of humanistic psychology, to appreciate who we are, and to fulfill our potential to become stronger advocates for what we may become.

About Marc Pilisuk, Ph.D.

Marc Pilisuk, Ph.D., is a clinical and social psychologist whose published works have covered topics in cognitive consistency, self-concept, community intervention, game theory, social problems, international conflict, ecology, and peace studies. He is a professor emeritus from the University of California and faculty member at Saybrook University. He is the author of 11 books and the recipient of state and national awards for teaching, research, and community applications. He was a founding member of Psychologists for Social Responsibility and of the first Teach-in.

The author wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Rebecca Ferencik and Salvador Cumigad in preparing the manuscript.