Keynote speaker at Saybrook’s 2017 graduation, James Whitfield, encourages graduates to “make America greater than it’s ever been.” See his speech below.

Thank you to the Saybrook trustees, faculty, staff, and distinguished guests. I am here because I love Saybrook, and I’m a huge fan of what Saybrook stands for. I’m a fan of the transformation that Saybrook is all about around health care and a learning experience, organizations, and community. The organization I run is also committed to changing the world through ordinary people.

I know that you have undergone a personal transformation as a part of your Saybrook journey. And as you graduate, I’m here to invite you to consider one more transformation as you take what you’ve learned and embark into the future. In January of this year, I had the opportunity to fulfill a lifelong dream and visit the Holy Land: Israel and Palestine. It was life-changing in a lot of ways, in ways I never would have imagined. One of the visits we made really transformed me, and I would like to share it.

The group that I was with visited an orchard outside of Bethlehem. These days Bethlehem is a part of the occupied territories. It’s outside of Israel. This orchard is owned by an Arab family that happened to be Christians, and surrounded by what Israel officially calls “neighborhoods” and what the rest of the world refers to as “settlements.” The family who resides there has documentation all the way back to the time when the Turkish empire ruled that part of the world. However, the state of Israel, due to security concerns, have been trying to get this family to move for the past 30 or 40 years. Now let me be clear. This is not a story about how Israel has real, legitimate security concerns because they do. News stories and international NGOs tell us that anti-semitism is up strongly around the globe. This is a story about what this particular family has chosen to do as they are caught in this historic tug-of-war.

You have to walk to this orchard because the Israel Defense Force, IDF, closed and blocked the road when the family was featured in a “60 Minutes” story. They started getting too many supportive visitors, and the IDF decided that nobody was going to slow that down. They would make it more difficult for people to visit. So you have to walk up this road for about a mile. As you walk, you come across a painted rock that says in Arabic and Hebrew and English the most powerful words I have ever seen. The words were, “We refuse to be enemies.”

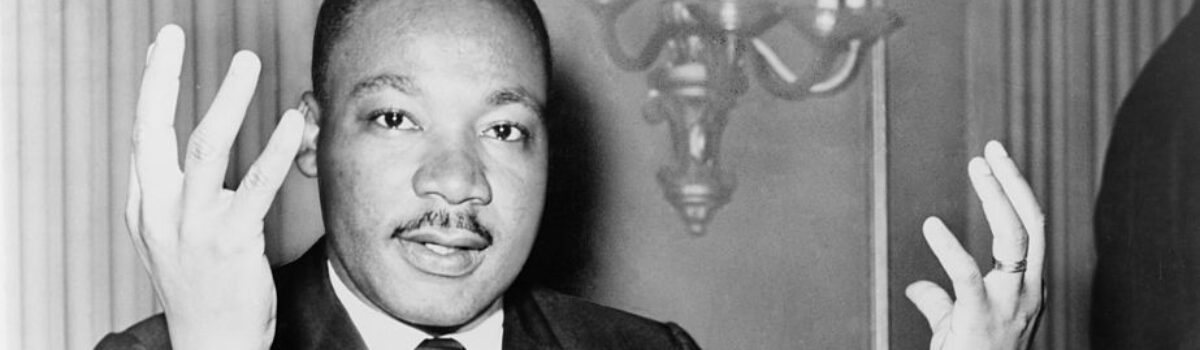

Roll that idea in your head for a second. “We refuse to be enemies.” For them, this isn’t just some motto. When the IDF bulldozes their trees, the family seeks to grow their compassion. When the Israeli legal system tells them that they can’t actually visit the courthouse, where their issue is being heard, they refuse to see an eye for an eye. When Israel cut off their water and limited the amount of rainwater they were allowed to collect, they still shower their opponents in love. What transformed me was their commitment to look beyond the current circumstances and focus on the final solution. To put it into words from Martin Luther King Jr., “We must learn to live together as brothers or perish together as fools.”

They’re committed to demonstrating what the right future looks like today. Now in my opinion this is a lesson that has been lost from the great transformational movements of the past: The commitment to move beyond protesting the offensive presence toward demonstrating an optimal future.

Let me give you a few examples from the 1960s Civil Rights Movement to explain what I mean. The power of a sit-in at a lunch counter was the fact that a black demonstrator and a white demonstrator sat together. They were showing the future. They were saying, “See, black people and white people can sit together and have lunch, and we are willing to suffer the consequences of showing that to you so that one day you can sit here with us.”

This is what the Freedom Riders did. Black and white people broke the interracial, interstate travel ban, by sitting on a bus together, singing songs, crossing borders. They could’ve staged a protest. They could’ve shut down all traffic on those roads in order to demonstrate, in order to protest how bad it was that they couldn’t ride together. But instead of standing still to protest the present, they were on the move to show our country where it should be headed. One of the things that people forget about Civil Rights marches is that black people frequently wore their Sunday best, and they walked hand-in-hand with their white sisters and brothers. They were saying “See, America, this is the future. There is nothing to fear other than billy clubs, fire hoses, and German Shepherds. And when you’re done with all of that, we’ll still be standing here ready to hold your hand.”

When people train to do nonviolent protests, they have to adhere to a set of things that were called The Ten Commandments. And one of those said that, “Our goal is not victory. It is justice and reconciliation.” Now the importance of this approach is crucial.

C.S. Lewis wrote that, “We who are ‘they’ to them do not exist as persons at all. And this applies as much to our opponents as it does to us. When we imagine them as unredeemable, we don’t work toward a future that redeems us all.” Demonstrations show us what our joint success looks like rather than merely protesting one side’s failure. We don’t demonstrate “against.” We demonstrate “for.”

Demonstration is an act of love for your enemies. The way Martin Luther King used to put it is, “Man must evolve for all human contact, conflict, a method which rejects revenge, aggression, and retaliation. The foundation of such a method is love.” Justice isn’t about fixing the past. It’s about fixing the future. Someone has to decide where your enemies fit in your transformed world. Will we relegate them to foot stools and doormats?

Most scholars agree that that approach paved the way for Germany’s defeat in World War I to Hitler’s descent in the second World War. And unfortunately we are still fighting Nazis today. Demonstration has a history and a future of success. This nation was born by imagining a shared future greater than the repeated injuries and usurpations that made our independence necessary. That’s the power behind, “All men are created equal” and unalienable rights, and life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. The founders weren’t confused. They knew that they weren’t writing about the existing, utopian president. They were laying the groundwork for an ever-improving future.

America isn’t perfect. I’m not sure it ever will be, but America has a future to strive for. Something worth demonstrating for. And I don’t want you to make America great again. I think that’s aiming too low. I want you to make America greater than it’s ever been before. That’s the foundational promise.

That’s the foundational promise of this crazy experiment, a government of the people, by the people, for the people. Before we ended our visit at Bethlehem, we were brought into a cave on his property. The cave is where his family lived hundreds, if not over a thousand years ago. This cave was not dissimilar to the caves scholars believed that Jesus or Nazarius was born in, not very far away. Sometime after the masters built a house on their property, the Israeli government stopped granting the ability permits so the cave is the only meeting location. We sat in this cave. He taught us a couple of Christian worship songs in Arabic, and then he lead us in singing that classic song of successful demonstrations, “We Shall Overcome.”

Imagine this. We’re sitting in a cave in Bethlehem with an Arab Christian in the occupied West Bank. Settlements are closing in on all sides, and he sings, “We shall overcome. We shall overcome. We shall overcome. I believe, deep in my heart I believe, that we shall overcome someday.” What’s transformative to me is not that we sang that song. It was the fact that for him, the “we” was not just Palestinians. And the “we” didn’t only include Christians. It also included his enemies, his opponents. And you know how I know? I know because he prayed for the people who were systematically trying to remove him from his land.

You want some information in this world? It starts with the transformation in your life that began here at Saybrook University. But going forward, it requires more. It requires refusing to be enemies. Demonstrating your most loving future. And that’s how we shall overcome someday. Congratulations Saybook’s Class of 2017. Let’s make this a more just, humane, and sustainable world.