According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the number of federal disasters rose 40% from 2000 to 2015. Social workers must be prepared to deal with the effects of many different kinds of crises, as climate change accelerates natural disasters, incidences of domestic terrorism rise, and the devastating impacts of COVID-19 compound.

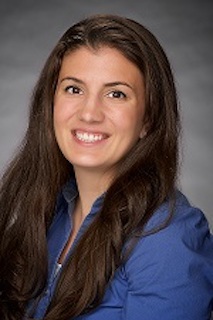

Trent Nguyen, Ph.D., in Saybrook University’s social work course 1020: Disaster, Trauma, and Crisis Intervention, takes on that task, preparing future social workers to work with clients who are coping with trauma as a result of major negative events. His course lays the theoretical framework that will enable his students to assist clients struggling with such complex issues as suicide, sexual assault, violent behavior, intimate partner violence, substance abuse, grief, and mass tragedies.

“Social workers deal with clients who have trauma all the time, especially with what we are going through globally right now,” Dr. Nguyen says. “Not just the pandemic, but domestic violence, substance abuse, and child abuse are all through the roof.”

His course covers timely topics such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sexual assault, bereavement, and school shootings. He also delves into the ways that cultural and social differences complicate social work, making cultural sensitivity an essential skill for any effective social worker.

“Help-seeking behavior is so different depending on one’s cultural and social background,” Dr. Nguyen explains. “Social workers have to be sensitive and humble to build rapport with their clients and cut across barriers and boundaries. These clients are looking for help but due to their background they may not know how to articulate that or how to ask for support. What we teach students is that with every person with whom they work, they must always start from scratch. They cannot make any assumptions whatsoever.”

Dr. Nguyen notes that social workers may see more than 15 clients in a day, and he teaches his students to be alert to the toll that can take on them. Burnout, vicarious traumatization, and compassion fatigue are common among social workers and can lead to issues such as substance abuse, distance from loved ones, depression, and numbness.

“When I was in school, we did not talk about secondary trauma at all,” he notes. “We were just trained to be present and provide quality services to clients. Now I want my students to realize that they also have some limitations. Most social workers have secondary trauma and they don’t seek help at all.”

Social workers often hear horrific stories and may struggle to leave those thoughts behind at the end of the day. A therapist who works with child abuse victims or a social worker helping military veterans may find themselves deeply impacted by what they learn in their line of work.

“For example, working with children who have been abused physically and sexually can impact professionals tremendously,” says Dr. Nguyen. “They bring these kids home with them, mentally and emotionally. They can’t get over it, can’t just forget it, and it can impact their personalities to a great extent. The reality is even though they don’t witness these events firsthand, their clients’ accounts impact them and the images stay with them.”

Dr. Nguyen teaches his students to build strong psychological boundaries to prevent compassion fatigue, and to use their peers and colleagues as a mutual support system. “One of the things I emphasize is that in this profession we cannot act as ‘Lone Rangers.’ We have to provide support to our peers and seek their support as well because there’s no way we can see dozens of trauma clients and at the end of day say that it doesn’t impact us at all,” he says.

Processing professional experiences with trusted peers allows social workers to tackle the secondary, vicarious trauma that would otherwise build up and calcify, leading to deeper impacts. Dr. Nguyen points out that acknowledging your limitations and accepting help and support will allow you to be a more effective social worker for your clients in the long term.

At the end of a year in which the U.S. saw hospitals overwhelmed, hundreds of thousands of deaths, millions of jobs lost, and a corresponding surge of domestic violence and mental health problems, social workers who are equal to the moment can make a huge difference. While global disasters may often be viewed as singular events, they are also composed of millions of personal tragedies in the lives of individuals who come from diverse backgrounds and disparate cultures. SW 1020 helps future social workers amass the tools needed to help these individual sufferers without compromising their own mental health and to be able to provide help by knowing when to ask for help themselves.

SW 1020: Disaster, Trauma, and Crisis Intervention is available to students in our Ph.D. in Integrative Social Work program. Learn more and apply today.